2017-07-03-python-协程和生成器

Table of Contents

1 生成器

1.1 简单的generator

python中的for很好用,但是如果循环的次数较多的话,需要占用很多内存。

于是就有了 generator ,需要在时候才计算。看看下面的的例子:

L = [x for x in range(10)] l = (x for x in range(10)) print L print l

generator可以例用next来访问:

l = (x for x in range(4)) print l.next() print l.next() print l.next() print l.next() print l.next()

结果如下:

0

1

2

3

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "/tmp/main.py", line 6, in <module>

print l.next()

StopIteration

可以看到,最后一个next抛出了一个 StopIteration 。我理解generator应

该是靠这个机制来完成它正确地打开方式的:

l = (x for x in range(3)) for i in l: print i

def fib(max): n, a, b = 0, 0, 1 while (n < max): print '---->b = %s<----' % b yield b a, b = b, a + b n = n + 1 g = fib(6) for i in g: print '====>b = %s<====\n' % i

1.2 定义函数做为generator

比较复杂的情况下,还可以定义一个函数做为generator,比如打印1到n的函 数:

def foo(n): for i in range(n): print i foo(4)

上面的函数稍威修改一下就是一个generator啦:

def foo(n): for i in range(n): yield i print foo(3) for n in foo(3): print n

如果一个函数中包含yield关键字,那么这个函数就不再是个普通函数,而 是一个generator

generator不像一般函数一样遇到return或者运行到最后返回。而generator 的函数,在调用next时开始执行,遇到yield返回,吐出yield的内容,再次 调用next又从上次yield后执行。

def foo(): print 'step 1' yield '[test] %s from yield' % 1 print 'step 2' yield '[test] %s from yield' % 1 print 'step 3' yield '[test] %s from yield' % 1 f = foo() print f.next() print f.next() print f.next()

2 python中的协程

协程和 生成器 类似,但是不同是的,生成器是数据的生产者,协程是数据的 消费者。

对应生成器的例子:

def foo(n): for i in range(n): yield i print foo(3) for n in foo(3): print n

这样可以定义一个协程:

def grep(pattern): print("Searching for", pattern) while True: line = (yield) if pattern in line: print(line)

和生成器一样,定义一个协程后,调用 next() 函数才开始执行,到

yield 后停止,然后调用 send() 函数给协程发送数据。协程收到数据

后继续往下执行,直到下一次的 yield 。

def grep(pattern): print("Searching for", pattern) while True: line = (yield) print 'recieve data ', line if pattern in line: print(line) print 'after if' g = grep('test') g.next() g.send('hi this is') g.send('hi this is test')

#!/usr/local/bin/python # coroutine.py # # A decorator function that takes care of starting a coroutine # automatically on call. def coroutine(func): def start(*args, **kwargs): cr = func(*args, **kwargs) cr.next() return cr return start # Example use if __name__ == '__main__': @coroutine def grep(pattern): print "Looking for %s" % pattern while True: line = (yield) if pattern in line: print line, g = grep("python") # Notice how you don't need a next() call here g.send("Yeah, but no, but yeah, but no") g.send("A series of tubes") g.send("python generators rock!")

3 理解一下python中的yield

import time def consumer(): r = '' while True: n = yield r if not n: return print('[CONSUMER] Consuming %s...' % n) time.sleep(1) r = '200 OK' def produce(c): c.next() n = 0 while n < 5: n = n + 1 print('[PRODUCER] Producing %s...' % n) r = c.send(n) print('[PRODUCER] Consumer return: %s' % r) c.close() if __name__=='__main__': c = consumer() produce(c)

可以看到 !n = yield r! 这一句,yield出去的r返回给send的发起者的。而

yield 本身的值赋给了n,n就是send发送过来的。。

执行流程是这样的:

- 主程序调用produce,c.next()执行就直接切换到consumer中开始执行。

- consumer中执行到yield,切换到produce从c.next()后继续执行,此时从 consumer中yield回来的值是空。也就是consumer中第一句给r的赋值。

- produce进入while,执行到c.send(n)。然后切换到consumer又从yield开 始执行。此时consumer收到的n是由produce发送过来的值。

- consumer睡一秒后给r赋值,然后重复while循环。到yield后吐出新赋值的 r给produce。

- produce打印返回值r,重复循环到c.send(n)。进入步骤3。

4 参考资料三写得太好了,我理解式的翻译了一些

就是它,建议英语可以的直接读它 Coroutines.pdf

4.1 更进一步理解生成器

4.1.1 一个python版本的 tail -f

import time def follow(thefile): thefile.seek(0,2) # Go to the end of the file while True: line = thefile.readline() if not line: time.sleep(0.1) # Sleep briefly continue yield line logfile = open("access-log") for line in follow(logfile): print line,

程序执行后,会一直在while中循环,如果文件结尾有插入数据,用yield吐出 来进行输出。输出完后再次进入follow中的while循环继续执行

4.1.2 生成器做为管道

结合 一个python版本的 tail -f ,来看看生成器做为管道的用法:

import time def follow(thefile): thefile.seek(0,2) # Go to the end of the file while True: line = thefile.readline() if not line: time.sleep(0.1) # Sleep briefly continue yield line def grep(pattern, lines): for line in lines: if pattern in line: yield line # Set up a processing pipe : tail -f | grep python logfile = open("access-log") loglines = follow(logfile) pylines = grep("python",loglines) # Pull results out of the processing pipeline for line in pylines: print line,

grep本身就是一个生成器,它接受一个安符串的pattern和一个生成器做为参

数。程序执行时,应该是一直在 follow 函数的while中循环等待。如果文

件结尾有数据进来,follow吐出数据,此时进入grep中的for,如果在这一行

中找到pattern,grep又吐出数据进行输出。完毕后又回到follow的while循环

中继续等待。

4.1.3 一个特殊一点的例子

注意看为啥中间的数字没有了。

def countdown(n): print "Counting down from", n while n >= 0: newvalue = (yield n) # If a new value got sent in, reset n with it if newvalue is not None: n = newvalue else: n -= 1 c = countdown(5) for n in c: print n if n == 5: a = c.send(3) print 'a = %s' % a

还需要注意的 :send后如果不接收它的结果,那么countdown中间有一次 yield出来的3将被丢弃。比如这样,结果里面是没有3的:

def countdown(n): print "Counting down from", n while n >= 0: newvalue = (yield n) # If a new value got sent in, reset n with it if newvalue is not None: n = newvalue else: n -= 1 c = countdown(5) for n in c: print n if n == 5: c.send(3)

4.1.4 简单总结

- 生成器为迭代器产生数据。

- 协程是数据的消费者。

- 不要把协程和迭代器混在一起。

- 协程与迭代器无关。

4.2 更进一步理解协程

4.2.1 使用协程写的 tail -f

import time def coroutine(fun): def start(*arg, **args): cr = fun(*arg, ** args) cr.next() return cr return start def follow(thefile, target): thefile.seek(0,2) # Go to the end of the file while True: line = thefile.readline() if not line: time.sleep(0.1) # Sleep briefly continue target.send(line) @coroutine def printer(): while True: line = (yield) print line, f = open("access-log") follow(f, printer())

程序执行后:

- 执行printer到yield返回follow。

- follow循环等待数据。

- 如果有数据follow发送给printer。

- printer输出数据后,再次从yield返回follow进入步骤2。

4.2.2 协程做为管道

import time def coroutine(fun): def start(*arg, **args): cr = fun(*arg, ** args) cr.next() return cr return start def follow(thefile, target): print 'begin follow' thefile.seek(0,2) # Go to the end of the file while True: line = thefile.readline() if not line: time.sleep(0.1) # Sleep briefly continue target.send(line) @coroutine def printer(): print 'begind printer' while True: line = (yield) print line, @coroutine def grep(pattern, target): print 'begin grep' while True: line = (yield) if pattern in line: target.send(line) f = open("kk.txt") follow(f, grep('python', printer()))

从打印可以看到,程序开始这样执行:

- 从printer开始执行,到yield后停下等待数据。

- 然后执行grep到yield。

- 然后执行follow进入while一直等待数据。

- 有数据后follow发送给grep。

- grep处理后,如果有合适的数据再发送给printer处理,完成后从yield返 回follow。如果grep没有发现合适的数据就直接从yield返回follow。

- printer收到数据后从再次停在yield后返回grep。然后grep返回follow进 入步骤3。

结合 生成器做为管道 ,生成器是使用迭代器从管道中拉取数据。而协程是使

用 send() 向管道中push数据。

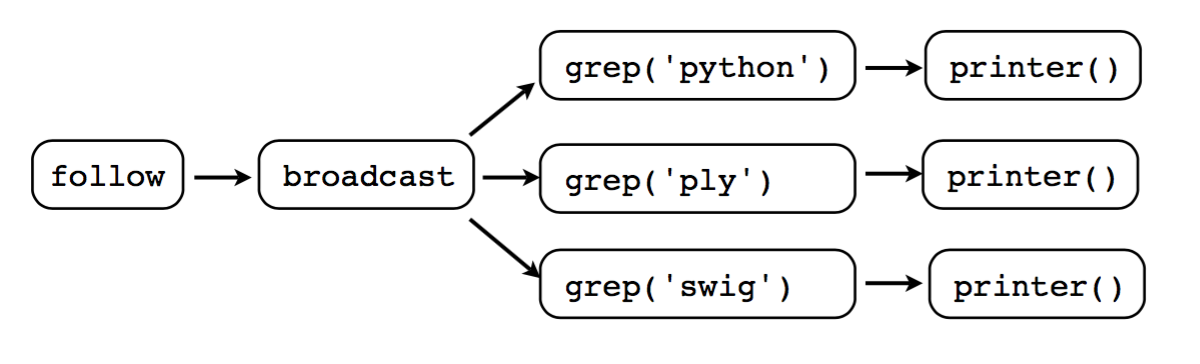

4.2.3 协程做广播

结合 协程做为管道 ,其实协程还有类似于广播的功能:

import time def coroutine(fun): def start(*arg, **args): cr = fun(*arg, ** args) cr.next() return cr return start def follow(thefile, target): print 'begin follow' thefile.seek(0,2) # Go to the end of the file while True: line = thefile.readline() if not line: time.sleep(0.1) # Sleep briefly continue target.send(line) @coroutine def printer(): print 'begind printer' while True: line = (yield) print line, @coroutine def grep(pattern, target): print 'begin grep' while True: line = (yield) if pattern in line: target.send(line) @coroutine def broadcast(targets): while True: item = (yield) for target in targets: target.send(item) f = open("kk.txt") follow(f, broadcast([grep('python', printer()), grep('ply', printer()), grep('simple', printer())]))

这个和 协程做为管道 的区别就只是到了broadcast,它send给了多个

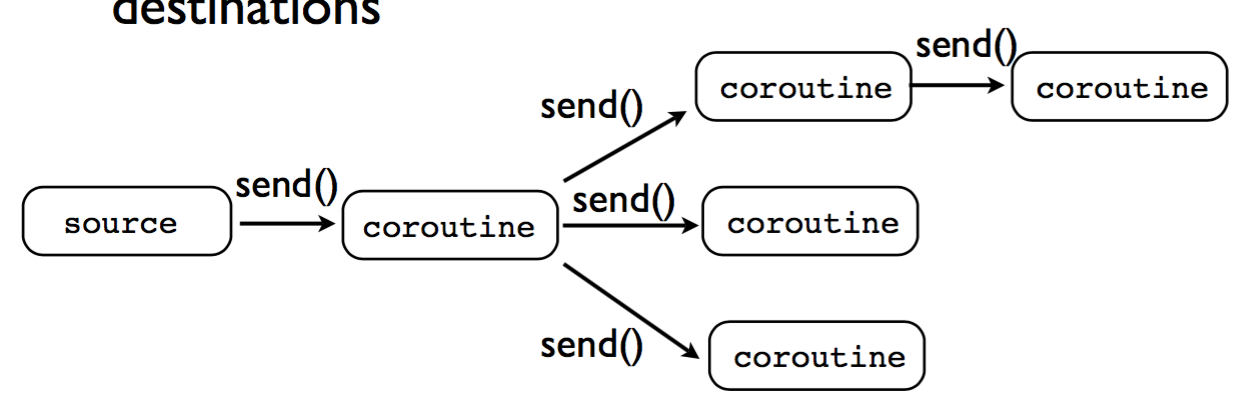

coroutine。这种情况的模型如下:

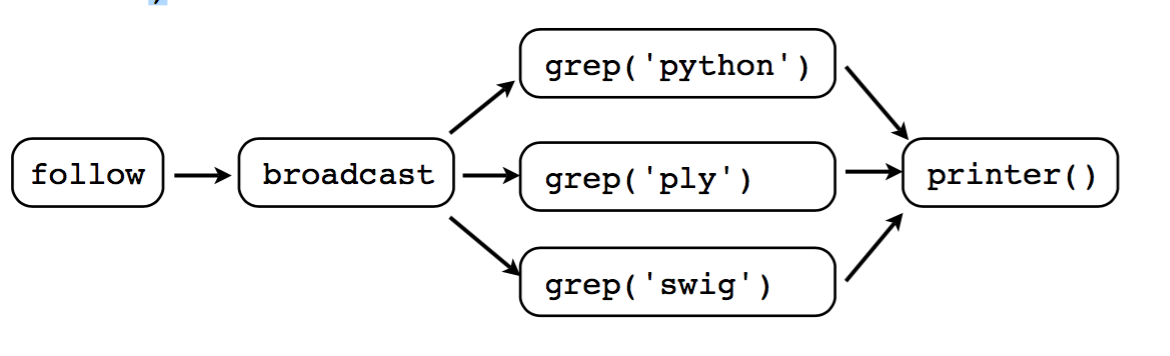

另一种模型是这样的:

f = open("access-log") p = printer() follow(f, broadcast([grep('python', p), grep('ply', p), grep('simple', p)]))

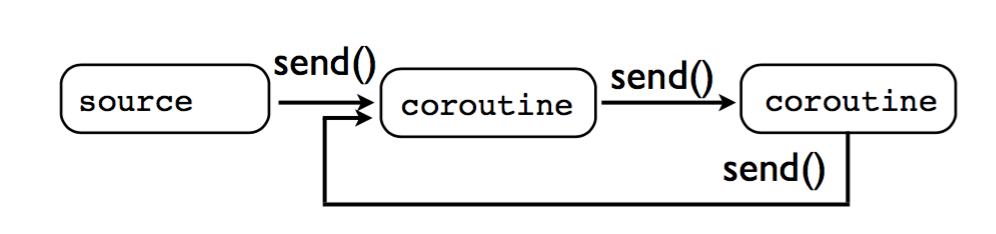

4.2.4 错误地使用协程

不能对一个正在执行的协程再调用 send() 。比如这样就会导致程序挂掉:

4.3 使用协程和生成器做成一个类似于OS的多任务系统

class Task(object): taskid = 0 def __init__(self,target): Task.taskid += 1 self.tid = Task.taskid self.target = target self.sendval = None # Task ID # Target coroutine # Value to send def run(self): return self.target.send(self.sendval) if __name__ == '__main__': # A very simple generator def foo(): print "Part 1" yield print "Part 2" yield t1 = Task(foo()) t1.run() t1.run()

调度器:

class Scheduler(object): def __init__(self): self.ready = Queue() self.taskmap = {} def new(self,target): newtask = Task(target) self.taskmap[newtask.tid] = newtask self.schedule(newtask) return newtask.tid def schedule(self,task): self.ready.put(task) def mainloop(self): while self.taskmap: task = self.ready.get() result = task.run() self.schedule(task)

第一个多任务的例子:

from kombu import Queue class Task(object): taskid = 0 def __init__(self,target): Task.taskid += 1 self.tid = Task.taskid self.target = target self.sendval = None # Task ID # Target coroutine # Value to send def run(self): return self.target.send(self.sendval) class Scheduler(object): def __init__(self): self.ready = Queue() self.taskmap = {} def new(self,target): newtask = Task(target) self.taskmap[newtask.tid] = newtask self.schedule(newtask) return newtask.tid def schedule(self,task): self.ready.put(task) def mainloop(self): while self.taskmap: task = self.ready.get() result = task.run() self.schedule(task) def foo(): while True: print "I'm foo" yield def bar(): while True: print "I'm bar" yield sched = Scheduler() sched.new(foo()) sched.new(bar()) sched.mainloop()

上面这个例子中,如果一个任务退出,会导致crash。所以需要处理一下任务 退出的情况:

from kombu import Queue class Task(object): taskid = 0 def __init__(self,target): Task.taskid += 1 self.tid = Task.taskid self.target = target self.sendval = None # Task ID # Target coroutine # Value to send def run(self): return self.target.send(self.sendval) class Scheduler(object): def __init__(self): self.ready = Queue() self.taskmap = {} def exit(self, task): print "Task %d terminated" % task.tid del self.taskmap[task.tid] def new(self,target): newtask = Task(target) self.taskmap[newtask.tid] = newtask self.schedule(newtask) return newtask.tid def schedule(self,task): self.ready.put(task) def mainloop(self): while self.taskmap: task = self.ready.get() try: result = task.run() except StopIteration: self.exit(task) continue self.schedule(task) def foo(): for i in xrange(5): print "I'm foo" yield def bar(): for i in xrange(10): print "I'm bar" yield sched = Scheduler() sched.new(foo()) sched.new(bar()) sched.mainloop()

这个例子中,scheduler可以看成是操作系统。任务中的yield就是操作系统中 的“中断”(或者是trap)。如果任务需要请求操作系统(scheduler)提供 的服务,即系统调用,需要带参数使用yield:

class SystemCall(object):

def handle(self):

pass

class Scheduler(object):

...

def mainloop(self):

while self.taskmap:

task = self.ready.get()

try:

result = task.run()

if isinstance(result,SystemCall):

result.task = task

result.sched = self

result.handle()

continue

except StopIteration:

self.exit(task)

continue

self.schedule(task)

这里的 SystemCall 就是系统调用的基类,所有系统调用都继承自它。在

mainloop中执行时,如果任务yield出来的是SystemCall,则先保存上下文

(当前任务和调度器)。下面定义一个返回任务id的系统调用:

class GetTid(SystemCall): def handle(self): self.task.sendval = self.task.tid self.sched.schedule(self.task)

那么此时任务应该这样定义:

def foo(): mytid = yield GetTid() for i in xrange(5): print "I'm foo", mytid yield def bar(): mytid = yield GetTid() for i in xrange(10): print "I'm bar", mytid yield

总的流程:,

- 调度器先调度到一个任务,任务yield出来一个系统调用。

- 调度器判断是系统调用没错后,保存上下文环境,然后进入系统调用执行。

- 本例系统调用中修改了任务自己的属性

self.sendval。然后重新把该 任务加入加绪队列。 - 调度器继续从就绪队列中取出任务进行执行。

- 再次调度到该任务时,它继续从yield处开始执行,而这次mytid就是系统

调用设置的

self.sendval。它是在执行时通过send发送过来的。其实 可以理解为系统调用的返回值就是它设置的self.sendval。

4.4 总结

yield总共有三个用途:

- 生成迭代器,数据的生产者。

- 接收消息,数据的消费者。

- 类似于操作系统的trap,实现多任务。

忠告就是: 不要尝试写一个带yield的函数来实现两个以上的上述功能。

5 参考资料

-

但是在A中是没有调用B的,所以协程的调用比函数调用理解起来要难一些。 看起来A、B的执行有点像多线程,但协程的特点在于是一个线程执行,那和多线 程比,协程有何优势? 最大的优势就是协程极高的执行效率。因为子程序切换不是线程切换,而是由程 序自身控制,因此,没有线程切换的开销,和多线程比,线程数量越多,协程的 性能优势就越明显。 第二大优势就是不需要多线程的锁机制,因为只有一个线程,也不存在同时写变 量冲突,在协程中控制共享资源不加锁,只需要判断状态就好了,所以执行效率 比多线程高很多。 因为协程是一个线程执行,那怎么利用多核CPU呢?最简单的方法是多进程+协程, 既充分利用多核,又充分发挥协程的高效率,可获得极高的性能。 Python对协程的支持还非常有限,用在generator中的yield可以一定程度上实现 协程。虽然支持不完全,但已经可以发挥相当大的威力了。 - 廖雪峰讲gevent

- 这里还有一个不错的英文介绍

Python通过yield提供了对协程的基本支持,但是不完全。而第三方的gevent 为Python提供了比较完善的协程支持。